By Rich Feldenberg:

The term species is viewed as a fundamental unit in biology. We are the species Homo sapiens, and we love to classify ourselves and other creatures into unique categories, giving them qualities that set them apart from other creatures. Charles Darwin’s evolution by natural selection gave the first proofs that all living organisms today descended from a common ancestor, which branded into an ever growing number of different evolutionary paths, resulting in a tree of life. The trunk being the last common ancestor (LUCA) and all the tiny twigs at the ends representing all species that have ever existed. But is this really an accurate view of the living world – each species of organism occupying its own unique little cubby, completely distinct from it’s fellows in the cubbies next door? We have learned a lot since Darwin’s important discovery of Natural Selection. Modern biology tells us that, while evolution is on firm scientific ground, the concept of the species is less so. We humans have a tendency to think in a discontinuous way – that things do fall into distinct categories – that there is a separate essence that each thing has unto itself. That may be one reason why evolution is a difficult concept to accept for some people, because if each thing has it’s own essence of being, you can’t change it into something else. This idea was demonstrated in an experiment where children were told a story about a witch that turned a frog into a rabbit. The frog now looked like a rabbit, acted like a rabbit, preferred to eat carrots and not flies, wanted to hang out with other rabbits, but when the children were asked if this animal was now a rabbit they said it was really a frog. It’s underlying froggy essence could not be altered by the witches spell.

It turns out that the concept of species is really not a discontinuous one at all. It is a continuous variable, and that may be a difficult idea to wrap your head around. In medicine some diagnoses are continuous and others discontinuous, and in some others it may be difficult to know for sure. For example, having 6 fingers on your hand is discontinuous (you either do or you don’t), but systolic blood pressure is a continuous value, with a range of anywhere from 0 to somewhere quite high like 250 or perhaps rarely 300, with most people being in a certain range, like from 100 to 140. So why is the species also a continuous variable? Isn’t a rabbit a rabbit, and a frog a frog? Certainly a human is a human, and not a chimpanzee, right?

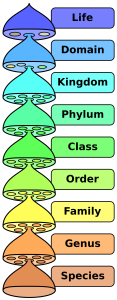

Well, keep in mind that names are just there for our convenience. How close they approximate reality may vary depending on the purpose of the name, and how good we are at understanding what we are describing. Ideally, a name would completely describe reality, but that will never be the case because a name is just a short hand way of talking about something else. Species tells us about taxonomic ranking. This is meant to help us determine which ancestors all the members of the species have in common, and how closely related those members are to members of another species. The problem arises in that the there is no defined line in the ground where one species ends and the next begins. One definition of species asserts that members of one species can not reproduce to have fertile offspring with members of any other species. This definition isn’t technically correct. The reason that this seems true most of the time, is that the many of the ancestral species happen to have died out, so it creates the appearance of very distinct groups of organisms (each in a separate and walled off little cubby).

Every generation is the same species as its parents and the same species as its own offspring. If this is true how could new species arise? It is precisely because the changes that occur due to evolution do so over much longer periods of time than a mere few generations. An organism could reproduce with a member of the prior generation, and if transported back in time to members from tens or hundreds of generations prior. At some point, however, there will be enough structural and/or behavioral differences that reproduction would no longer be possible.

Say that we took an organism back in time (it could be any organism, even a human). When we took him or her back 50,000 generations we find that he/she was able to reproduce with the contemporary population, but couldn’t reproduce with the individuals from 100,000 generations earlier. Now if we go back 50,000 generations from our starting point and take a subject from that era (one that could easily reproduce with our original organism) and then take him or her back to 100,000 generations before our starting point (50,000 generations before this individuals time) we find that it can reproduce with an individual from that long distant time period. So the original could reproduce with a subject from 50,000 generations ago, but not 100,000 generations ago, and the individual from 50,000 generations ago could reproduce with one from 50,000 generations ahead or behind its own time.

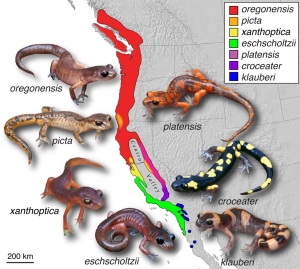

Since in the real world, those ancestors are mostly extinct it give the illusion of a discontinuous landscape of species. Richard Dawkins gave an excellent example in his book, “The Ancestors Tale” when he described ‘the salamander’s tale’. In that example Professor Dawkins described several species of salamander that live along a ring of high elevation in Central California. The ring forms a physical geographical structure that makes the species adjacent to any salamander’s location available to them, but prevents the species from interacting with species on distant parts of the ring. At the southern end of the ring are two distinct appearing species Ensatina eschscholtzil and Ensatina klauberi. E. eschscholtzil is brown and lauberi is spotted, and the two species, while in contact with each other do not interbreed – the very definition of separate species! That’s all well and good except that as you go up north on either side of the ring there are more species still, and each of these can reproduce with the species neighboring it.

It’s likely that the ancestral species arrived at some time in the past in the north. Two descendant populations emerged, one going south by the eastern route and the other going south by the western route. If all those other species on the ring had gone extinct we would be left with two species that could not interbreed and there would be nothing very special about the story. Those other species did not die out, however, and there is a continuous ring of salamanders that can reproduce with others of similar species, except in the case of the two southern species. As Dawkins says in the book, “Strikes a blow against the discontinuous mind”. The situation for these salamanders reveals what the situation would be like for any species (human included) if all of our ancestors were alive today. There would be a continuous stream of organisms that can interbreed with those close to them in time, but only over longer time scales do differences add up that make them distinct enough that interbreeding is no longer possible. The sides of the ring represent a common ancestor, diverging and over time becoming two separate species, but having a path of “able to interbreed” individuals all the way down.

In another post, I’ll illustrate another problem with the “tree of life” concept. In actuality the tree concept is complicated by “lateral gene transfer” – basically genes being swapped by other organisms of different types. This is very common in bacteria, but also seems to happen to some extent in more sophisticated organisms. In any case, the idea of species should be used as a useful placeholder, but has important limitations.

Reference:

1. Species, Wikipedia.

2. “The Ancestor’s Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution”, Richard Dawkins. 2004.

3. Another clever Mesign by Mother Nature. Darwin’s Kidneys. July 8, 2015.